God’s mercies are new every morning, so every day there’s a reason to preach about God’s generosity. But if you’re looking for a particular opportunity to speak about giving or to launch a stewardship campaign, some dates in the lectionary invite this focus.

The readings on the following Sundays, from the year B lectionary readings (running from Advent Sunday 2023 to Christ the King Sunday 2024) provide particular opportunities to talk about giving and generosity. The Revd Jenny Dawkins, our Generous Giving Advisor, provides short notes below.

The Diocese of Rochester, in partnership with St Augustine’s College of Theology and the National Giving Team of the Church of England produce a weekly, bite-sized resource for preaching about generosity; find out more information and sign up for a weekly email here.

Do contact us if there are any resources you’ve found especially helpful so that we can share them with others.

3 December (First Sunday of Advent): Mark 13.24-37, Isaiah 64.1-9, Psalm 80.1-8,18-20 and 1 Corinthians 1.3-9.

The first windows of Advent calendars have been opened, the advent candles lit. The eager anticipation that characterises this season is sharpened by the darkening nights and a deep longing for light.

Christmas adverts and playlists in the shops chime with a certain sort of expectation too – “holidays are coming”, “Santa Claus is coming to town”.

But anticipation comes in a variety of shades. A letter to a headteacher: “Ofsted is coming”. Preparation for dear – or complicated, or demanding – visitors. A date circled on a calendar: dentist’s appointment. The promise of a breakdown truck when you’re by the side of a motorway on a rainy night.

Our reaction to an announcement of someone’s arrival depends on a few things – who’s coming? How soon? Why? Are we ready?

More than once, Jesus tells his disciples a story about servants waiting for a master’s return. Today’s gospel reading is one of these; this master has entrusted his servants with his home, his authority, and his work. He has set a watch on the door. Who knows when he’ll return?

These stories situate Jesus’ hearers in expectancy. But what character will that waiting take – hopeful? Careless? Fearful? Urgent?

Isaiah expresses an imploring, even impatient waiting – “oh, that you would rend the heavens and come down!” His expectancy is based on Yahweh’s covenant faithfulness, his khesed –“no eye has seen any God besides you, who acts on behalf of those who wait for him” (Isaiah 64.4) The Psalmist echoes this plea: “Awaken your might, come and save us” (Psalm 80.l2). On behalf of their people, in the midst of waiting, these writers are expressing an urgent hope for a rescuer, one who’ll enact justice, loyal love, the fulfilment of promises of shalom made long ago.

At Advent, we enter into this longing and pray these prayers alongside those who are today longing for peace, for justice, for rescue, for wholeness.

In the birth of Christ, we see promises fulfilled – God comes down in the fullest and most unexpected way – as a baby. As Mary sang, in this birth, God has come “to the aid of his servant Israel, to remember his promise of mercy, the promise made to our ancestors, to Abraham and his children for ever.” (Luke 1.54-55)

Compare this generous, powerful, faithful Coming with the coming of Santa….

Like the master in the parable, Jesus gathered disciples and entrusted them with his work. He made them a dwelling place, a home for His presence, and gave them an authority that is humanly beyond them. Because of His generous giving of Himself, they – and we today – “do not lack any spiritual gift as you eagerly wait for our Lord Jesus Christ to be revealed” (1 Corinthians 1.7).

What does this all have to do with generosity and giving?

- Will we be faithful with all God has entrusted to us, stewarding our time, talents and treasures on behalf of a faithful and generous master, who desires justice, fulness of life, peace and hope for all?

- In Christ, we have been “enriched in every way” (1 Corinthians 1.5). Will our lives reflect the generosity of our God?

(See the Bible Project resources on Advent for more reflections).

10 December (Second Sunday of Advent): Isaiah 40.1-11, Psalm 85.1-2,8-13, 2 Peter 3.8-15a and Mark 1.1-8.

Today’s readings share a common thread: creation itself, heaven and earth, responds to the coming of its King.

Isaiah, and then John the Baptist, prophesy that His coming will be literally seismic. Mountains brought low, valleys lifted up. Peter shares this epic perspective – the heavens and earth will be laid bare in fiery destruction. The Psalmist sings of creation springing into fruitfulness as righteousness goes before the Lord to prepare the way for his steps.

God’s intention for creation is for fruitfulness and abundance. But human greed and acquisitiveness has resulted in de-creation – the destruction of environments, species, and weather systems. So what does the Advent of the coming King, His intention for and impact on creation, mean for us today?

Isaiah suggests that, like John the Baptist in our gospel reading today, our preparation for Christ’s coming happens in relationship with creation: ”in the wilderness prepare the way for the Lord; make straight in the desert a highway for our God”. Even in apparently fruitless places, like a wilderness, there is work to be done – hard, sacrificial work, participating in setting straight what has become crooked. The promise is that God’s glory will be revealed. As the letter from Peter puts it, “in keeping with his promise we are looking forward to a new heaven and a new earth, where righteousness dwells.” It remains a wonderful mystery exactly how our work of preparation and God’s gift of recreation will marry together when the new heavens and the new earth are revealed. But our present creation doesn’t appear to be destined for abandonment, rather, for renewal.

As Tom Wright puts it “the fact that God has renewed creation in Jesus and intends to renew it from top to bottom in the end should have immediate implications for our care of the planet. If someone gave you a wonderful painting to decorate your home, it wouldn’t be very respectful if you used it as a dart-board, or as a chalkboard for the kids to draw on. And if someone said that didn’t matter because the original artist would come one day and mend it and clean it up, you might think that wasn’t the point. But that’s how we have often treated God’s good creation.”

Or more succinctly “Jesus is coming, plant a tree!”

Creation care can be expressed, among other ways, in practices of ‘enough’, a rebellion against consumption, including (maybe especially?!) at Christmas.

Holding lightly and giving generously, including to help your church move towards Net Zero carbon, could be part of our advent practice today, living and giving generously for a promised future that is in the hands of a creative God.

More practical ways in which you might care for creation during Advent here.

Further preaching notes on Advent and creation here.

A homegroup Advent study on creation here.

21 January (Third Sunday of Epiphany): Genesis 14.17-20, John 2.1-10.

Nearly 1000 bottles of wine, according to most calculations. The miracle recounted in today’s gospel reading points to an extraordinarily generous God, a God of abundance. Preachers find a variety of nuances to celebrate in this.

Canon Kenneth Padley, Treasurer of Salisbury Cathedral, calls this “a wine lake”. He goes on:

“the Hebrew prophets regularly portrayed the end times as an age of unprecedented, unimaginable, fruitfulness, overflowing yields of oil and wine. … The total volume of booze across the six jars was between 120 and 180 gallons. That is a vast quantity, especially for a humble village wedding. So the message is about superabundance, God’s generosity overflowing beyond limit.

Such liberality of God’s gifts, says John, is a characteristic of the age of Jesus.”

It is a sign that points to so many profound and liberating things about the God whom Jesus reveals to us; His delight in and concern for our own personal life and loves, attested by His presence at the wedding feast, His abundant generosity in more than meeting our needs in the midst of everyday life, His call to us to move from the mere outward purity, symbolised by the water for ritual washing, to a transformation of inward joy, symbolised by the wine.

But most importantly, this sign points to the gift of His very self, His own heart’s blood, given once for all on the cross and received by us in communion.

This generosity demonstrates Jesus’ compassion for this particular family – their running out of wine risks huge shame. In this powerful (lockdown era) sermon, Rev’d Sally Hitchiner pans out to see a message for God’s people, Israel: “They were supposed to be hosting a party for the world to see the goodness of God but they had been so worn down by the constant oppression of richer nations that they had shrunk back into meagre survival and petit bourgeois judgementalism. THEIR wine had run out”. The miracle points forward to the wedding feast of the lamb, and

“the great, vast reservoir of God’s joy, the wine… now freely flowing”.

Debie Thomas reflects that “the wedding in Cana story is not — finally — a story about scarcity. It’s a story about abundance. Lavish, excessive, extravagant abundance. ……But what strikes me here and now, as I struggle to reconcile a Bible story about abundance with my contemporary reality — both personal and global — of scorching scarcity, is the pivotal role Mary plays in the story.

“They have no wine,” is a line I can get behind.

“They have no money.” “She has no cure.” “He has no friends.” “I have no strength.” Mary’s line is a line I repeat daily, in endless iterations, for myself and for others. It’s the line I cling to when I feel helpless, when I have nothing concrete to offer, when Christianity seems futile, when God feels like he’s a million miles away. It’s the line that insists against all odds on the mysterious power of telling God the truth in prayer.”

The reading from Genesis describes a glimpse of a ‘blessing economy’, (a phrase from the Bible Project’s discussion about Melchizedek) where generosity and blessing are the currencies exchanged – and once again, they are embodied in wine, as well as bread. Melchizedek is a mysterious figure, but the 3 verses devoted to him here are outweighed enormously by his significance as the first Royal Priest of the bible, one in whose priestly line Jesus lives.

Some have seen in this encounter a Christophany – Melchizedek’s name means ‘King of Righteousness’, and his title, ‘King of Peace’. In the text, he has no genealogy and no succession until Christ comes. Even without this thought, though, he can be seen as a godsend to Abram. He provides for him and he blesses him, as a priest of God Most High (El Elyon). As the Bible Project notes, “the King of Sodom comes to take [see v21], but Melchizedek, the King of Salem, comes to give and to bless.” Abram, in grateful response, enters into this blessing economy, bringing him 10% of all his goods – a tithe. No-one has compelled him to give this – his giving is thankful, voluntary, and systematic – proportionate to what he owns. He models here a response which will become characteristic of the Jewish people as they respond in gratitude to God.

So, how might we respond?

- Will our generosity reflect that of our generous God? Will we host a party for the world to see God’s goodness?

- Like Abraham, will we enter the blessing economy freely, cheerfully, and with a thoughtful, planned, proportionate approach?

4 February: Psalm 104.27ff, Colossians 1.15-20

Both the Psalm and the Epistle reading speak of God’s creative and sustaining power – God’s good provision for God’s creation. They further recognise God’s re-creative power – the Spirit that renews the face of the earth (Psalm 104v30), and Christ, the first-born from among the dead reconciling all things to Himself, bringing living hope to the whole created order.

To know and worship this overflowingly creative Triune God, whose endlessly generative love cannot be overcome by brokenness or death, is to be built up in confidence in God’s generosity – and to be released in our own.

25 February (Second Sunday of Lent): Mark 8.31-38.

By this point in the gospel, the tone is changing and the journey to the cross has become more evident. Jesus has begun to prepare His disciples for the suffering to come: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me.” Dietrich Bonhoeffer, in The Cost of Discipleship writes “when Christ calls a man, he bids him come and die”.

Ultimately, though, Jesus’ message is a hopeful one. In Christ, self-giving is not a route to less but to more abundant life. Laying down our preferences, agendas, reputations, and even our belongings means they lose a hold on us, freeing us to fullness of life in Christ.

7 April (Second Sunday of Easter): Acts 4.32-35

Resurrection Economics

How many times have you left a celebration with a slice of cake that was going spare? Or hosted a party and found yourself with more bottles than you started with? After the most recent bring and share lunch at my church, I had to find room in my freezer for what was still generously given at the end of the feast (after loosening my belt an extra notch to make room for just one more spoon of jollof rice…).

Perhaps I’ve just been especially fortunate, but in my experience, there’s something about a party that brings out the generosity in people. Whether it’s a happy contagion, or the natural overflow of givers gratefully receiving and receivers thankfully giving, a party creates its own economy – and its theme is abundance. (This great Bible Project video picks up the story.)

——-

After the resurrection of Jesus, an unexpected, expanding party of His followers, drenched with the Holy Spirit, dripping from baptism water, found themselves living in a new economy too.

As Ron Jones observes, Luke “mov[es] seamlessly from speaking of the apostles’ testimony about the resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ to their generous acts of kindness [4v33-4]. Luke makes an undeniable connection between the empty tomb and compassion. He has just introduced us to resurrection economics.” He goes on: “when the early Christians grasped the reality of the empty tomb, a revolution of generosity took place. They could have broken into small groups to discuss the deep theological implications of the Resurrection, but they didn’t—not at this time, anyway.” Instead, they budgeted, ate, and drank differently.

The real Jesus had risen from a real tomb, had eaten real fish and sat round a real fire, and the first impact for the first followers was for their real possessions – real fields, real money, real houses. It made for the creation of new, real friends. Willie James Jennings notices “Money here [was] used to destroy what money normally is used to create: distance and boundaries between people.”

It’s as though these disciples had found incalculable treasure in a field, and somehow their estimations about worth and possession had entirely changed. They’d seen God overturn what they could expect about the future and suddenly thoughts of savings or security had acquired a different frame. And their bank statements revealed the transformation. Sam Wells writes “Their use of money was the most visible way others could see what they believed about Jesus’ resurrection.”

This right-side-upping of economics by the inbreaking power of God’s new life doesn’t make things more comfortable, and especially not for those who are doing pretty well by the status quo. For anyone with money, influence or power, resurrection economics is the last thing you want (to paraphrase Simon Perry).

Resurrection economics is disruptive. Willie James Jennings again: “Luke gives us sight of a holy wind blowing through structured and settled ways of living and possessing and pulling things apart. People caught up in the love of God not only began to give thanks for their daily bread, but daily offered to God whatever they had that might speak that gracious love to others.”

So what about me? Does my bank account make visible what I believe about the resurrection?

Changed by Eastertide, I want to choose to look at my bank account, my home, my table, my purse with resurrection-saturated eyes. To trust God in the present because He’s brought the eternal future into it – and the future is abundant. To give with more open hands because what remains isn’t what’s in my purse, but faith, and hope, and love – and the greatest of these is love.

Jesus is risen, and everything is changed. May it be so for me too. Amen.

21 April (Fourth Sunday of Easter): 1 John 3.16-24

What is love? This funny, touching poem by poet Brian Bilston is made up entirely of Google auto-completed searches about love: Love in the Age of Google.

In today’s reading, John doesn’t google to ask what love is, but looks to Christ and His cross: “this is how we know what love is: Jesus Christ laid down His life for us”.

Christ’s giving of Himself, laying down his life for our rescue, defines love. It also sets a model for those who follow Christ – to express love with a whole life: “not with words or tongue, but with actions and in truth”.

Our love of God and neighbour can be seen by how we choose to use our time, talents and treasures, our lives laid down to serve another, following the way of Christ.

30 June: 2 Corinthians 8.7-15.

“See also that you excel in this grace of giving” (2 Corinthians 8.7).

Paul’s encouragement to the Corinthian church fits into a longer story.

The church had eagerly embarked on giving to their poorer, parent church in Jerusalem when famine had hit Judea. He’d recommended how to do this in 1 Corinthians 16.1-5 – collect money when you come together each week and set it aside. They’d somehow waned in enthusiasm, so Paul writes to call them again to a glad giving practice springing from gratitude and mutuality of relationship.

This Bible project podcast takes up the story, looking at how Paul seeks to persuade them:

- look across to the example of the (much poorer) Macedonian church, who beg for the privilege of sharing in giving;

- look up – most importantly – to Christ, who “though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich”;

- look around – the nascent church is supplied through sacrificial relationships, those who have more give more, in order to supply the needs of those who have less.

The Corinthian church is a comparatively well-supplied congregation, but their zeal is outpaced by that of other, poorer churches. We might see parallels in our Western context today.

There are a variety of resources available to support preaching on 2 Corinthians. The Giving in Grace project gives sermon reflections, including from Rt. Revd John Packer who in 2000 served as Chair of the National Stewardship committee of the Archbishop’s Council. He notes “Paul is not prepared to command the Corinthians (v.8) but he is prepared to challenge them. …He does not simply say that it is up to them to decide how much to give. He challenges them to demonstrate the love they claim to have… That is what Jesus has done for me. He demonstrated his love by giving all of himself. We enter into the richness of that giving. So we are freed to give of ourselves because we have the ultimate security of knowing his love.”

The series also has accompanying bible studies.

This ‘Generous June’ series includes a sermon outline on this passage from David Williams, Bishop of Basingstoke. He paraphrases Paul’s approach as “If you’ve got plenty, you ought to be giving plenty…. Give, if you like, until it begins to cost us something to give.”

A Generous July

The readings for July provide the opportunity for a month focussed around giving. This gives more space to expand on themes: suggested titles are given below.

7 July: Travel lightly, Mark 6.1-13, 2 Corinthians 12.2-10.

In today’s gospel reading, Jesus’ disciples are sent out to share in his mission. They are told to travel light – no packed lunch, spare clothes or cash. They will have to ask for help and hospitality as they go. It’s a striking contrast to how we often conceive of sharing in God’s mission today. We usually go equipped and expect to offer help, rather than ask for it.

What the disciples are being asked to do is empty themselves, lay down the power of possessions, and come vulnerably among people who may or may not welcome them or the message they carry. They are following the way of Jesus.

To empty ourselves and travel light feels risky, reckless, even. To rely on the help of others feels not only vulnerable but presumptuous. But when we come with emptied hands, we become freer to move with God’s Spirit. We’re humbler, less attached to possessions and position, and more dependent on what Jesus does give – His authority and His presence. I’m reminded of something I heard once from a follower of Jesus, a minister, who had had to flee their home in a conflict situation, without possessions:

‘when Jesus is all you have, you find that He is all you need”.

He had not chosen his situation, but in it, he had found God abundantly faithful to His promises, and discovered an unshakeable and completely unexpected joy.

This is the paradox of the Christian life – those who cling onto their lives will lose them, those who give them away will save them. Paul writes of this in his letter to the Corinthians, today’s epistle reading. He has developed, through experience won in pain, a bewildering reflex. He rejoices not in triumphs but in “weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions and difficulties.”

Perhaps it’s similar to what Leonard Cohen sings in ‘Anthem’:

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

How do we take a first or a next step on this unlikely, counter-cultural journey of self-emptying? Considering our financial giving is a key part of our discipleship of Jesus, and giving beyond what is comfortable, giving so we notice the difference, puts us in a position to receive the truth of this paradox for ourselves. Will we accept God’s ‘I dare you’ and take courage to travel light?

14 July: Worship extravagantly. 2 Samuel 6.1-5,12b-19, Ephesians 1.3-14, Mark 6.14-29.

Today’s gospel passage provides a gruesome counterpoint to the joyful worship in the Old Testament reading. King David offers joyful worship, dancing and singing, to Yahweh. King Herod also brings a sort of worship – the grim offering of the head of John the Baptist, to a girl he’s pridefully objectified and to whom he’s made a rash promise.

Different kingdoms mean different offerings. What – or who – we worship impacts how we worship – and ultimately impacts us. We become like the object of our worship, as the psalmist recognises in Psalm 115. As Greg Beale puts it “What people revere, they resemble, either for ruin or for restoration.”

I was once told a story, by someone who worked with people experiencing homelessness in Cape Town. One of the people he got to know had been addicted to heroin. The drug had cost him his family, his home, his health – everything. He came to know about Jesus, and recognised the choice that was offered to him: “do I worship heroin, which has taken everything from me, or do I worship Jesus, who has given everything for me?”

Paul’s letter to the Ephesians bursts with thanksgiving for God’s generosity: “Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus, Christ, who has blessed us in the heavenly realms with every spiritual blessing in Christ.” (Ephesians 1.3).

Our worship in response is expressed through our bodies, our song, our wallets, our attention, our affection. We could try to summon up all our willpower to make determined efforts of generosity. Instead, like Obed-Edom, whose story we glimpse alongside David’s, we are given the opportunity to host the generous presence of God by His spirit (Ephesians 1.13-14). In His presence, we’ll find our lives begin to reflect our identity as adopted children (Ephesians 1.5), and the family trait of generosity will become part of our inheritance.

21 July: Become God’s Dwelling Place, 2 Samuel 7.1-14a, Ephesians 2.11-22.

“You are being built together to become a dwelling in which God lives by his Spirit.” (Ephesians 2.22)

God isn’t looking for David to build him a physical dwelling place. Rather, God promises to come and dwell in David’s family. “When David offers to make God a home, God explains that his home has always been with his people.” (Jane Williams, in Lectionary Reflections).

Paul now writes to the Ephesian church, Gentiles and Jews reconciled into one body, about their part in this extraordinary vocation.

The church is a unique, diverse, international, multi-ethnic, multi-cultural community. We are utterly interdependent, one new body created out of many (Ephesians 2.15). This is expressed in multi-faceted worship, loving and hospitable relationships – and in generous financial giving. We are drawn to share what we have, giving sacrificially for the whole people of God to flourish.

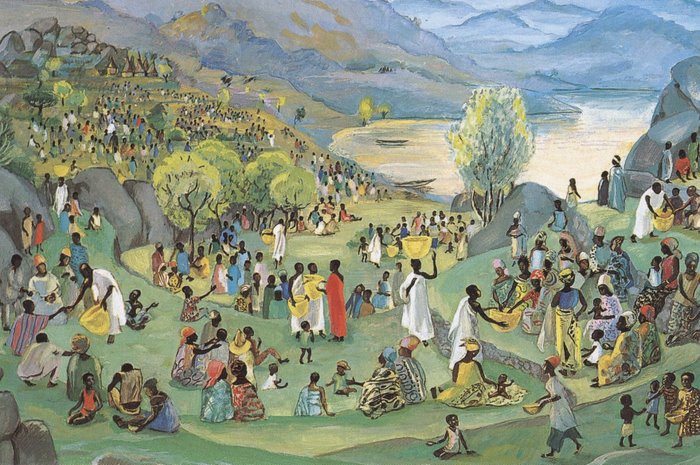

28 July: Feast Abundantly. Ephesians 3.14-21, John 6.1-21.

“The need is overwhelming. There isn’t enough to go around.”

This can feel like a familiar story. Not enough food, not enough time, not enough help, not enough limited resources. Exhausted staff or volunteers, stretched funds. A vast crowd, hungry for food, healing, connection or hope.

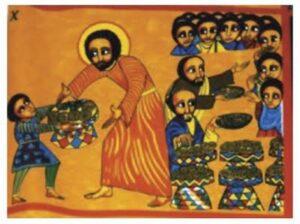

Image from https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=57902

In our gospel, we see Jesus sitting on the mountainside with his disciples, a hungry multitude coming into view. We might come to sit here too, in company with Jesus, knowing the reality of our need and our inadequacy.* We listen for his words.

Image from https://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=48287

Jesus asks his followers “what shall we do?”

Not “what shall I do?”, taking the miracle entirely out of our hands. Not “what shall you do?”, burdening us with something too weighty for us to carry. But “what shall we do?” – Jesus inviting us to partner with him. “Where shall we buy bread for these people to eat?”

As the gospel writer says, Jesus already knows what is possible, but He chooses to involve His beloved friends.

God gives us the opportunity to be involved in extraordinary things.

This is His every day invitation to us, one He is ready to meet with “His power… at work within us”.

Philip makes speedy calculations in his head. Andrew looks around. As he brought his brother Simon to Jesus, now, he brings someone else – a boy with a small packed lunch.

Ethiopian icon: artist unknown

It’s not nearly enough. Not the disciples’ gifts, their expectations or faith. Not the boy’s food. None of it is nearly enough for this crowd of hungry people.

But what the disciples, the boy and the crowd learned that day is that what they have is not the end of the story with Jesus. What we bring is not all there is.

When all we bring is hunger and inadequacy, our poor gifts, Jesus does more than we can ask or imagine (Ephesians 3.20). We bring scraps and He transforms them into a feast. We bring our ordinary, mixed up, inadequate selves and He makes us, “together with all the saints” (Ephesians 3.18), into a church.

‘Nothing is God’s favourite material to work with’.

We are invited to join the party, to bring our hunger and receive more than enough. To experience this picnic of underserved grace every day.

In a different sermon on the same passage, Nadia Bolz-Weber writes: “We so often feel shame about our lack, when in fact, our lack is what God wants from us. It is always our poverty. Because when all we have is strength and virtue and self-sufficiency we become functional atheists…maybe believing God exists but not acting as thought it really matters.“

Paul prays for Ephesian church not because they are already full, but because they have a need. It’s into empty hands that God pours “out of his glorious riches” (Ephesians 3.16).

Jesus gives, and he gives more than enough. This is a miracle of revelation. The provision of bread in the wilderness, miraculous and abundant, seems to point people towards Jesus’ identity – the same God that provided manna from heaven. God is recognisable by his generosity.

Tabha chapel floor mosaic, Sea of Galilee, 4th century

JD Greear asks “did you ever wonder what Jesus would have done if he didn’t have five loaves and two fish? … He could have done the same miraculous work with a bread crumb and a fish fin. The amount we give matters far less than the spirit with which we give.”

He goes on to reflect on what we gain when we give.

“Most of us think generosity is something God wants from us, but… it is something he wants for us.”

JD Greear

The little boy with the packed lunch gained so much more than he gave; 12 baskets of leftovers were collected so presumably he had more than enough. But more than that, he got to join in with Jesus’ miraculous generosity close-up. This boy, reflecting God’s generous character, gets to participate in a miracle that every gospel writer tells us about, and by which Jesus is revealed – a greater gift than he could have ever imagined when he left home that day.

* This collection of global art provides images of this story to meditate on. While enjoying the images, listen to this song, Two Little Fishes and Five Loaves of Bread by Sister Rosetta Tharpe. This version by Odetta is from an album ‘Shout Sister Shout: A tribute to Sister Rosetta Tharpe”. A version by Sister Rosetta herself is here.

** This tumblr collects images and music from around the world that reflect on this miracle.

Generosity in Ordinary Time

4 August: Ephesians 4.1-16

Unity in the body is a theme threaded through Paul’s letter to the Ephesians. As the Bible Project puts it “God’s plan was always to have a huge family of restored humans who are unified in Jesus.”

Paul spends the first half of the letter overflowing with praise at God’s extraordinary plan of a multi-national, multi-ethnic, reconciled family, now revealed in Christ. Paul’s tone is of astonished thankfulness at God’s grace which has enabled Paul to play a particular part in God’s purposes.

Now Paul turns to reflect on what a fitting response might be to this wonderful gift.

He urges followers of Jesus to “keep the unity of the Spirit through the bond of peace” (v3). Each should generously exercise the gifts they have been given, in service of the whole body, that all should be built up. Unity in Christ will be a marker of maturity.

As individual churches, and as a diocese, we will have some sense of what this might look like in practice. As a Diocese, the Parish Support Fund is one way of expressing mutuality. It funds clergy and lay training, to build up pastors and teachers in their work, supports pioneering ministries, including among children and young people, equipping apostles and evangelists. Vital services such as Safeguarding mean that each part does its work (Ephesians 4.16) safely and well.

8 September: Proverbs 22.1-2,8-9,22-23, James 2.1-10[11-13] 14-17.

The book of James invites us to a thought experiment – how would we react to different visitors to our churches?

It’s a good provocation: the gospel of Jesus invites us into a whole new way of relating to one another, rejecting the patterns of the world that favour wealth and influence.

Worldly patterns can have a powerful hold on us – John Wesley said that “the last part of a man to be converted is his wallet”. Giving generously is one way of pushing back against that hold.