Those of us in Bletchingley in 1965 didn’t of course know at the time that the short, laughing, dancing African who came to live in the Clerk’s House next to Selmes the Butcher would turn out to be a loved, honoured and respected world figure, a living embodiment of a Christian who taught us that God created us and loves us to the end.

So how did it happen? To cut rather a long story short, Desmond was spotted as a bright boy and supported by Fr Aelred Stubbs CR and Fr (later bishop) Trevor Huddleston CR of the Anglican Community of the Resurrection headquartered in Mirfield, Yorkshire but with a House in South Africa. Desmond often told the story of how when they first met, Trevor raised his hat to his mother – unheard of during apartheid.

Fr Stubbs and the Dean of Kings, University of London arranged for Desmond to read for a theology degree and plans were laid. Desmond came to the UK in 1962 on his own. A lonely start, but he was soon found a curate’s flat in Golders Green and Leah and two children arrived and together they enjoyed the freedom from police and passes unknown in South Africa. He met Martin Kenyon, Secretary of the Overseas Students’ Trust who delighted in introducing Desmond to English life and it was through him, as a friend of my parents, Uvedale & Melanie Lambert – who were also good friends of the Community – that the plan was made in due course for the Tutus to move to Bletchingley while Desmond studied for a higher degree at Kings in, surprisingly this time, Islam.

Thus it came to pass that the Tutu family – by now five of them Desmond, Leah, Trevor, Naomi and Mpho – were fetched by Uvedale and the Rector, Ron Brownrigg, in a Land Rover and brought to their new home. Theresa joined them later on. Bletchingley at the time had rarely seen a black face and the arrival of the Tutu family was quite an event. But the parish responded magnificently, they furnished the house and welcomed the family generously and they soon got used to seeing Desmond roaring around on his Vespa and preaching in St Mary’s. People clubbed together to send Trevor to the Hawthorns. When he went back to South Africa they gave him a car, and when he went to be bishop of Lesotho they gave him a horse! Desmond gave to Bletchingley his infinite “capacity for love and joy”, as Shirley du Boulay wrote in her biography Tutu: Voice of the Voiceless (1988) and he gave us an understanding of the political realities of South Africa and the terrible injustices of the police state of apartheid.

The parish church then was rather ‘higher’ than he had been used to in Golders Green and he enjoyed the colour and ceremony of that tradition – by nature he was extravagant and the ritual was a natural dance for him. Bletchingley was a great experience in that regard and he loved its open and ecumenical approach where Anglicans, Roman Catholics and Methodist often worshipped in St Mary’s and people of all backgrounds in the village got together. “God loves you,”, he said “and you can’t do anything about it.” No escape from the love of God was his recurring theme. And Mrs du Boulay records that he was once seen dancing in the starlight quite alone, after Midnight Mass celebrating the joy of Christmas.

But the time came all too soon for the family to return to South Africa and the village mourned their departure. Twenty years later as Bishop of Johannesburg when he returned to Bletchingley to preach he told the congregation “how back in South Africa, surrounded by hate, the memory of their love had protected him ‘like a ring of fire’. The press, expecting a political sermon, were there in force and astounded at the way Bletchingley treated Desmond as one of their own”. (Mrs du Boulay again.)

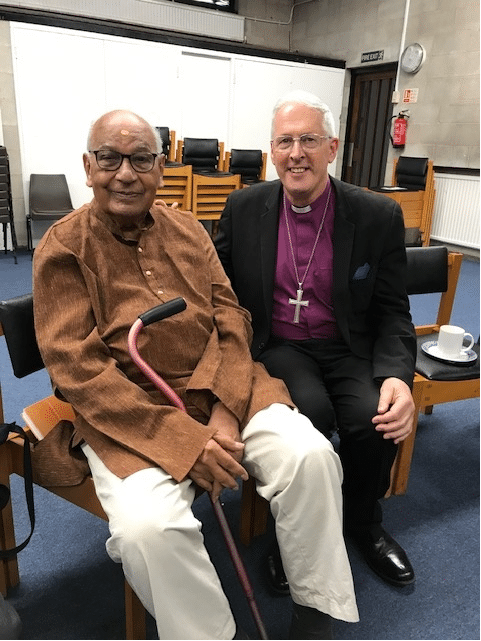

In fact Desmond came back on quite a few occasions that I remember and it was always a joy to see him either in the parish or sometimes in London when he was passing through and his assistant would telephone to ask if we could come up – often for a quick eucharist (and what a thanksgiving) in his hotel room before we joined him and others for supper. And I know that many other friends, some from Bletchingley, had similar invitations or would go to South Africa for special occasions. A particular joy for our family was when he came to South Park in 1992 to preside at our daughter’s wedding when the wedding rings on his bible slipped off down the central heating grating and had to be rescued by Tim. Cassandra is the same age as Mpho and they had been on the school run together in Bletchingley along with Melissa Remnant at Pendell Manor.

Desmond was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1981 and that, together with his position as bishop and subsequently archbishop, did give him a measure of security in his fight against apartheid and his friendship with Nelson Mandela was a great strength, but not before he had experienced fear and suffering at the hand of the police himself. His work for reconciliation was hard and not always well received but it was a most courageous effort to bring to and keep peace in South Africa besides creating a model for mediation and reconciliation in other world conflicts.

I remember meeting hm once off a flight at Heathrow and as we made our way to the car park a woman rushed up to him and just brushed his coat. All she wanted was to touch the hem of his garment. Such was the goodness and holiness of his presence.

Thank you, Desmond, for loving us and teaching us about God’s love. May you rest in peace.